|

It looks so simple. Four short words, I understand them all, and yet, it feels so familiar to be uncertain in the face of this question.

To want is powerful. So it behooves us to know what we want. Wants are impulses. They can be momentary, frivolous, wants can morph into longing, and they can be a compass to our life purpose. They can also be driven by the teachings of our society, parents, religion, and education, such that what others want us to do overrides our connection with what we want. Impulses are signals from the nervous system and can originate from one of three places: the internal guidance system (also known as our intuition, following our hearts, or body wisdom), instinct (a somatic response to a stimulus), or learned patterns of avoidance (moving away from something we’ve been taught is dangerous - also known as internalized systems). Internal guidance system impulses are the ones we are often looking to follow when we are searching for our own way. They are the pull to do the thing from our congruence, and from befriending our will. They are the things that are “correct” for us, even if they’re difficult or require us to travel through the unknown. Instincts are a somatic response to a stimulus. They bypass the conscious brain and create an impulse to pick up our foot when we step on legos, or to swerve when the car in front of us suddenly stops. Learned patterns of avoidance are internalized responses to stimuli based on “how the world works.” This can be wildly different for different folks, but gets at our internalized (but learned) rules about what we are “allowed” to be like. This is where we can say “I followed my heart” but really mean “I operated according to the rules that said I shouldn’t disappoint someone else.” The bottom line is that learned patterns of avoidance are not always wrong, but they can be. The learned patterns of avoidance that are incorrect undermine our ability to trust our internal guidance system because the impulses it creates can often feel similar. One of our tasks in deepening our self-understanding and finding our congruence is to learn to tell one from the other. This is an experiential task. One that we do through paying attention, through befriending ourselves, through learning how to recognize our congruence (or lack thereof). It is something we spend our whole lives doing. The Mothers that help me when I'm looking for my congruence, to know what I want, are Wind Mother, Island Mother, and Mountain Mother. The three of them provide the skills and hold me in the tasks of unhooking from those learned responses, noticing what is arising in me, and befriending my own will. They are available to you too, should you want to call on them.

0 Comments

Over the last year I apprenticed myself to the land burned in the CZU fires with the intention of learning how to navigate catastrophe. This year, other land in the US west is burning. May the land teach us how to witness and how to respond, not just to these fires, but to all of the catastrophes unfolding before us. On August 16th, 2020 fires were ignited by lightning in the mountains north of Santa Cruz, California. My first visit to the burned area was on September 10th. I stepped onto the land and immediately noticed that the ground was different. It was otherworldly, made of fine ash that puffed around my boots and stuck to my pant legs. The foundation of everything had been changed, the good nourishing duff of the forest floor was gone. It is like this, isn’t it, when a catastrophe happens? That the very ground seems to shift under our feet. Everything feels off kilter, unbalanced, even surreal. And finding our bearings can feel impossible. It requires more attention, more care, to walk across this now unfamiliar terrain. I would not know for weeks or even months what had lived and what had died in the fire. Trees that looked like they survived would still die and fall. It took time for the catastrophe to fully play itself out, for the losses to be known and the true extent to be revealed. I had long thought of catastrophe in nature and in my life as momentary, confined to a single place in time. But they are not, or not always. There was a deep quiet in the forest as the effects of the fire continued to unfold. Animals had fled, including humans. What could not leave was destroyed, like the snail shells that turned to dust when I touched them, and bones that fell apart when I tried to pick them up. While it was clear that things had changed drastically, it was unclear how it would continue to unfold, what would be left, what would be revealed, what would be truly lost. This is a liminal space, the in-between, where the unknown is palpable.

The land left me with a strong need for presence, for being with what had happened, for witnessing the continued unfolding of the event. The request I felt from the land was for dedication, to keep returning, to follow and notice. So often I have rushed over the uncomfortable and devastating parts of life, trying to hurry on to a place I was more at ease. But here, nature was going at its own pace, so much slower than mine. And the request was for me to slow down and be with the forest. What does life look like when we go through something difficult? What happens in me when uncertainty is the only thing in front of me? What do I do in the in-between time? A key piece of Landscape of Mothers is that we want to remember to give ourselves credit for what we're doing. Remember that we're in a world that devalues caring for others, whether that's children, the elderly, or the disabled. Needing care is often seen as a characteristic of weakness. But the world needs true caregivers. We need one another as a fundamental part of our humanity. And so it's helpful when we're in caregiving situations that we make sure that we celebrate and honor our own work. This is downright countercultural in a time where we are all familiar with the term Mommy Wars. We can go about this differently. Landscape of Mothers gives us a map to do this differently. But, I digress.

When we are willing to celebrate, when we honor our caregiving work, we can be simultaneously building from the shore of "this-doesn't-work-I-want-it-to-be-better" and from "woohoo-I-know-what-does-work". And building on what works is so much easier than trying to create an entirely new foundation for something we can only hope will be better than what we've got goin' on! And... my invitation to you is to write what you are celebrating below. No celebration is too small! A shower without an audience, one meal that felt nourishing, something begun that feels like it's going somewhere good... it's all part of honoring what we're in. Once you have your celebration, notice the reaction in your body. Notice and name the sensation. Archetypes can help us get unstuck when we feel like we are out of options through giving us perspectives or lenses that we might not otherwise entertain. This removes us from the habitual neural patterns that have us stuck in a loop that doesn't feel good. Patterns in which we have to lose or let go of something that feels important. Archetypes can also help us choose a path when we feel overwhelmed. By looking to an archetype that has a particular perspective and personality, we have perspectives available to us that we don't have to create. That is, we don't have to know what we want the situation to look like, we can just know that we don't want what's happening. We step into the perspective of an archetype and try it on. What works for us? What is possible? Does this feel better? What can we do with this understanding? It's important because when we are parenting we are so often sure of what we don't want, and not as sure of what's possible. If we also have to create that whole dream world of what we do want and how to get there... it can just be overwhelming. And limited. Working with archetypes invites us to step back a bit, give more room to the situation, and to slow down. From there we are able to locate the context of what we're doing. We can see more clearly, we have more options, and we have choice about what we can do. We see different facets of what's important to us, where we're stuck, where we're having success (oh... never forget that last bit... notice and appreciate your successes! Don't gloss over them... they are the strengths that you build with!).

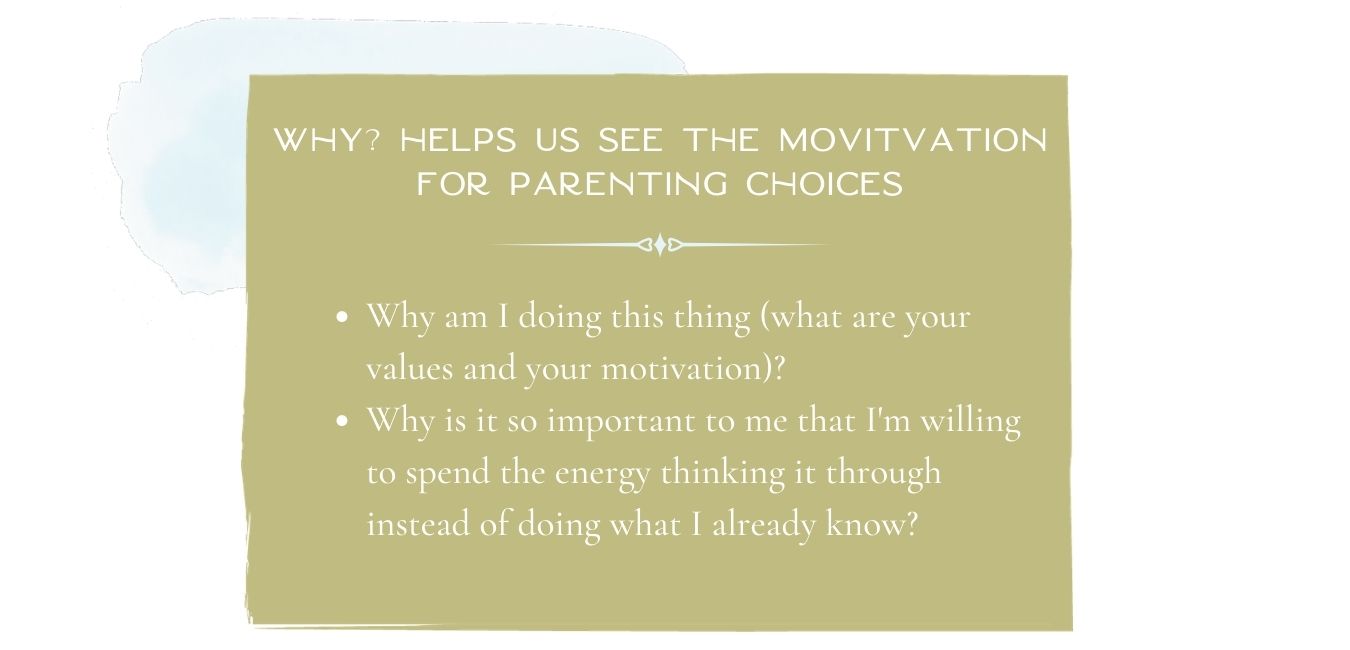

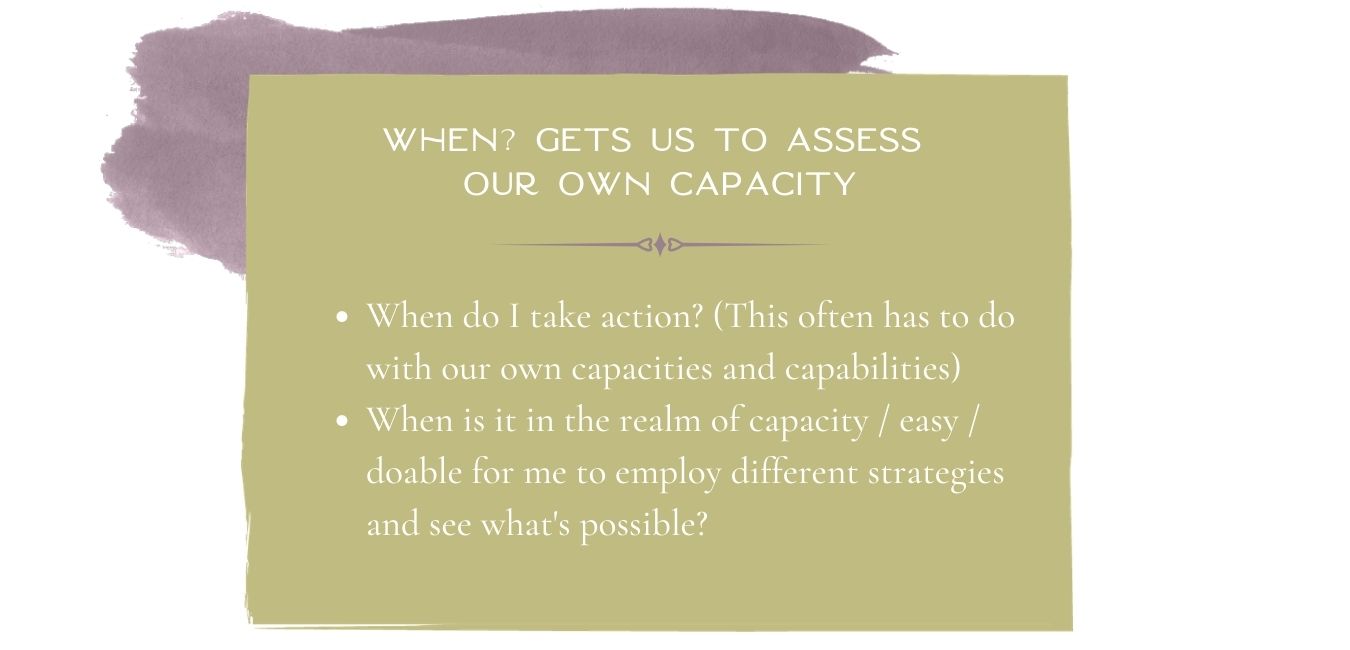

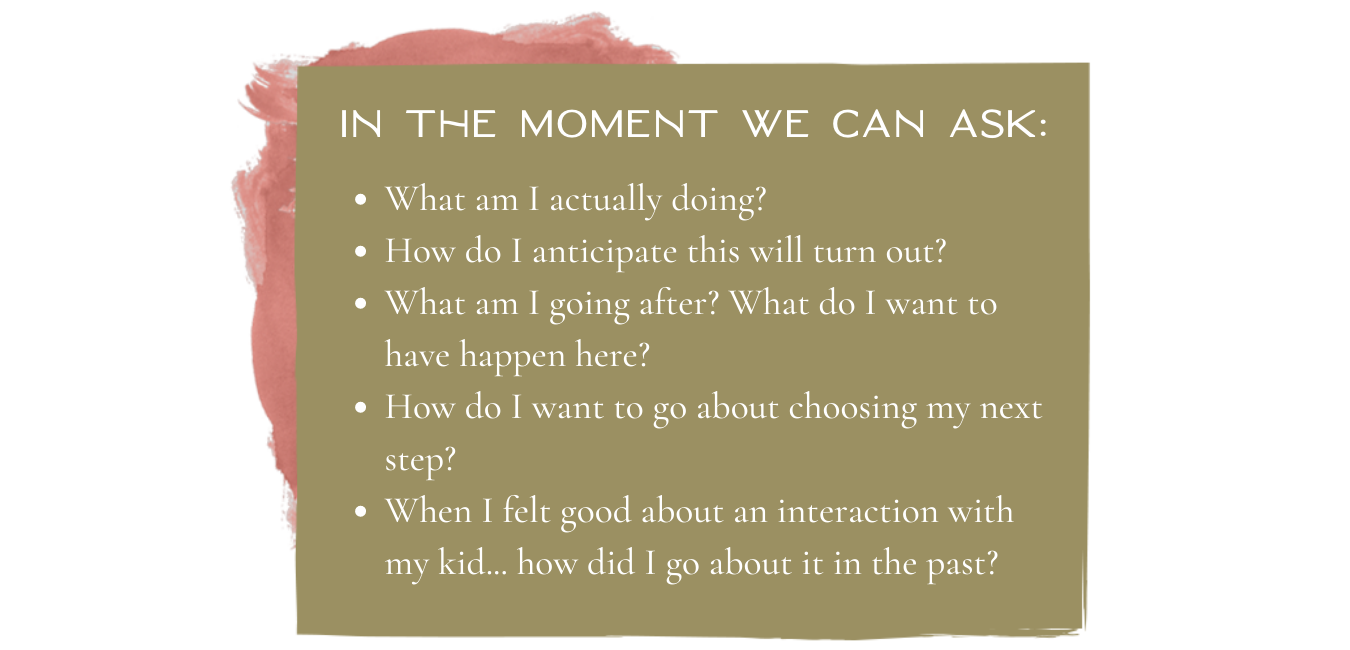

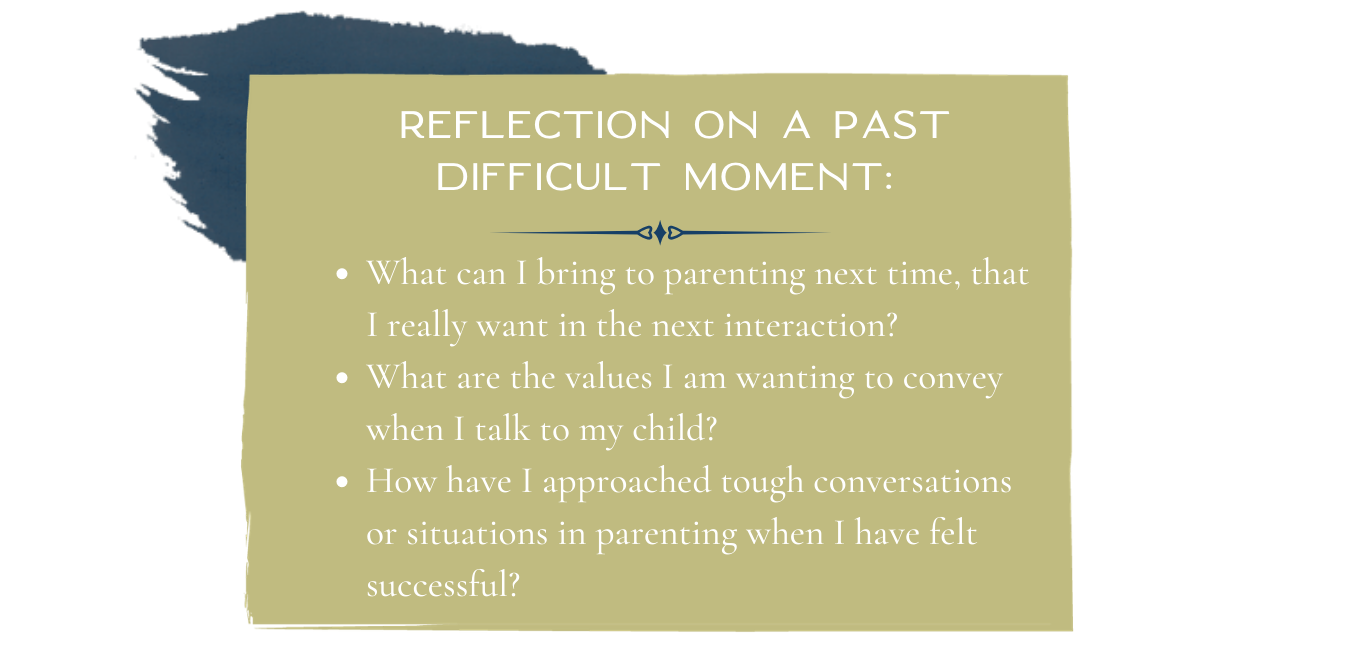

Archetypes are particularly helpful where we are in situations that feel hopelessly tangled, messy, and every question is met with more questions. By stepping into the perspective of a particular archetype we get a finite perspective that has particular possibilities and we are able to manage some understanding or insight from it. The perspective of the archetype has an inherent understanding and knowledge there to build on. When we personify the archetype we can relate to their perspective easily and we can often find guidance in the perspective. We are not obligated to act on that guidance, but the simplicity of having an offering of a way to proceed can open the power of the brain to locate other possibilities. This was not available to us when we were feeling stuck or overwhelmed. I explore this further in a YouTube Video if you'd like more of my thoughts on archetype as parenting help. You can also sign up for my newsletter if you'd like to hear more. In ecology we characterize how things work through the concepts of structure and function. Structure is the stuff we see when we ask ourselves WHAT or HOW. Structure is the behavior, the context, the goal, and our intent. It is how we approach a situation, what we bring when we come, and how we use our voice and our body to engage. Function is about the process, it is the flow and relating we hope to do when we come to a situation. It may overlap some with structure around our intent. WHY and WHEN are the questions that help us explore function. Sometimes these questions lead us back to our childhood pain. So, tread lightly here. The intention of asking these questions is not to retreat old painful pathways. Instead, what we want to do is skim off the surface of the facts. For me, I was alone a lot as a child. This was both because I grew up in the 1970's and 1980's when that was common... and because I suffered some big traumas during those years for which I did not receive help. Therefore, I have deep values for presence, connection, and being helpful (with consent). To ask HOW and WHAT we are investigating the structures, environment, and context of our parenting choices. When we ask WHY and WHEN we are locating our values, motivations, and assessing our capacity to show up fully for what's in front of us. The remaining questions of WHO and WHERE are relevant questions, that I'll answer when my next book comes out! Teaser: it has to do with where the relationships are (as in, is it a family relationship, community, or with yourself) and who else might be involved (a dependent, peers, or individuals in an hierarchy). This post is part of a video that I posted (LOM on YouTube) in a series on Landscape of Mothers Foundations. The topic is Structure and Function... and this post and the video are specifically about Structure. What we do and how we do it in our parenting relationship. When we enter a place in our parenting where we want to do things differently than what we have known, we are entering the unknown. It helps if we take a look at the places that we have done well in the past, or felt good about how we handled a situation, and we can apply what we know about what works to the new situation before us. I find it helpful to look at where things have gone well and ask myself a couple of questions about it. There are two parts to what we're investigating, the structure and the function. That is, we conjure a time in our minds in which we walked away feeling proud of how we handled some parenting moment... and we want to investigate the structure, or what was in place, what are the facts, and how it played out. We also want to understand that function, or why we did what we did, and what the context was. This video (LOM on YouTube) talks about the structure part of our inquiry. We're going to use the "Who, what, where, when, why, and how" questions... and the two particularly related to structure are WHAT and HOW. For me, I find that an approach that contains curiosity and questions is helpful (and so getting myself to that place before I approach my kids is crucial... and I really need to tie a string around my finger so I can remember it). As always, this requires some discernment. It requires that not only do I come with questions, but that I bring the presence of openness with them. Kids can tell when the question falls more along the lines of "what the hell are you thinking?" rather than, "hey, wanting to check in and ask about what happened yesterday. How do you feel?"

When we come to a situation where we're not sure what to do, or we have an urge to do it the way our parents would have (that wouldn't have felt good to us), we can take a pause and ask ourselves what we have done in times where the kids have responded well. If we already have answers because we've thought about it, we can respond better when a situation takes us by surprise.

The waves came in consistent and strong. Clearing and cleansing. Usually the rock doesn't rise that high above the sand. The waves take the sand away during the winter storms, and deposit it back in the seasons of gentler waves. I watched as the ocean took sand away, subtracted, removed. Erosion.

The ocean comes to clear the beach when it's time. The Ocean Mother contains the Death Mother... the one who says goodbye, the one who grieves. And the quote above is what she left me with. What does it mean to have regard for someone? For yourself? The origin of the word regard is Old French and is made up of “re-“ which means back, and “garder” which means “to guard”. Regarder (the Old French verb) means “to watch”. So, regarding is watching or seeing in a way that is protective, that circles back to safety. The way I think of it, regard is about allowing someone to have their full humanity. That includes the imperfections, the suffering, the disagreement, the joy and their right to choose their perspective. It means that they are not disposable, that it is not OK to shame or punish them, to tell them what their experience is, and it means that banishment or exile is not on the table. Regard does not, however, require me to agree with them. Holding someone in their humanity means that our fundamental orientation is that they deserve respect and dignity. If I disagree with them I do not have the right to infringe on their humanity. If I feel hurt by them I still do not have the right to infringe on their humanity. Regard is being able to set boundaries or make agreements without denying the humanity of any of the people involved. Regard is like love, in that it’s both a place we stand to see another person, and the way we behave toward them. Like love, if we don’t act in a way that lets the other person know how we feel, then they may not believe in our regard or love. Regard is both the things we hold to be true about someone from our vantage point, and our behavior that communicates our perspective to the other person. It is the acknowledgement of the person, and it is the circling back to the safety and validation of being held as a human worthy of respect. We can also have self-regard. This is the perspective that I hold for myself… one of self-compassion and acknowledgement of my own humanity. The associated behavior is treating myself with respect, honoring that I am having a (likely imperfect) human experience, but that I do not deserve to be shamed, abandoned, or punished… not even by myself. Self-regard holds me to treating myself respectfully, and it holds my inner dialogue to a standard of nourishment and protection rather than criticism and berating. The degrading voice in my head is not mine, it cannot coexist with self-regard. Ultimately, regard is embedded in a culture of shared humanity, care, and connection. It is also the bedrock of such a culture. Regard also feels like a lighthouse, a beacon, for how I want to be in the world. When I don’t know what to do, or how to handle a situation, I can ask myself what regard would look like if it were present… and I can do that. Oh so many heartbreaks in a human life. How do we do it? How do we keep living with broken hearts? How do we ever resolve them? Forgiveness? Strength? Moving on? Honestly, I've learned so much about tending to heartbreak lately. Certainly the current state of the world gives us all fodder for heartbreak work. It returns us to our smallest selves, our vulnerable and soft places. These places are not aligned with the "just do it" mantra of our society... the encouragement to just keep going... to not pay attention to the stuff that bothers us. But, one thing I do know, is that if we don't tend to our heartbreaks, they accumulate. Tending opens a soft space for being... like laying on the couch with a million blankets, wrapping up in a comforting gentleness, a bit like being held like a small child. Yes, to tend is to hold gently. It is to be with, to sit down next to something or someone and hold their hand. It is not to fix, or to advise. The wisdom of tending gives space to the heartbreak to do its work. To lead the heartbroken through the landscapes of grief and anger... arriving at a hill with a bit of a view... a place that provides context. It takes time to make this journey, and tending is the attention we give that liminal space so that we can find our way through. This is deeply important work. the tending of heartbreak.

I have always struggled with the concept of forgiveness. And, I can tell you that I've only every found genuine forgiveness (or anything that could look like it) on the other side of tending to heartbreak. Tending takes showing up again and again, for things that feel like nothing... sitting under the tree, lighting the candle, or sorting stones. Tending is being with a process at the particular place that it is, and allowing it to run its course on its own time. This is hard. It takes longer than you think it will. It moves at the pace of the natural world. And it cannot be rushed. Tending is also one of the biggest gifts we can give to one another. It builds relationship because it moves slowly and is done one small bit at a time. It creates reliability because it requires us to come back over and over. And tending creates connection because it is based in care and devotion. Sometimes I notice that more than one of the Landscape of Mothers archetypes will address whatever I'm turning over in my mind. This fall, as is common at this season, change seems to be at the forefront of people's minds. If we listen to the land as we move into autumn, we can learn about how to release, how to let go, and how to grieve. Several of the Landscape Mothers hold ways of being with change, because the quality and tone of it can be so varied. This encourages us to inquire into what nuance of change we are experiencing in our internal world as we see the seasonal change happening in nature. The Sun and Moon Mother is about the kind of change that is a rhythm, a cycle, some way that we repeat and anchor our lives. She holds the cycling of seasonal activity, celebrations, or simple recurring tasks that we perform that help us know where we are in the scheme of things. Those rhythms might be always having a holiday meal at a certain person’s house, or the constancy of what makes up the meal itself. Or it might be giving a loved one a hug before they leave the house for their day. It doesn’t have to be big, but it does repeat again and again… and so it is the constancy of our rhythmic movement in our lives. The Wind Mother is the one who introduces change as an environment shift. She picks you up and carries you somewhere else. She is the kind of change that instigates a beginning. She is the seed sower, the interrupter, the creative spark. Things change with The Wind Mother around in a way that the environment is different, more than maybe you are changed by it. While you may mature here, there is a continuity between where you were and where you are not. The Desert Mother is the change of loss. You don’t get picked up and put somewhere else… you are fundamentally altered within. This is the realm of grief of the things that did not happen, or happened overwhelmingly, such that things will not be the same again. You are not the same. It can look the same on the outside, but nothing is the same on the inside. Things die here. It is a broken open kind of landscape. Potentially every one of the Landscape Mothers has her version of change or resistance to it. But I see that these three Mothers have a particular kind of relationship to change that helps me locate the nuance of what I’m navigating in my life. They describe not only the way I might be seeing or feeling the changes, but help me identify what emotions I might carry about them. Do I feel anchored and supported, excited and maybe afraid, or am I grieving a loss? What might that mean will be most helpful for me in being where I am? What do I need to give myself in order to be true to myself? What might I want to ask for from others? |

Author: Jill CliftonHi, I'm Jill, creator of Landscape of Mothers. I'm here to talk about breaking family patterns of harm so that we can parent our children in ways that support them becoming fully themselves. I'm happy to have you here! Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed